There is an article in today’s Daily Telegraph by Ben Lawrence which startled me. We’re all familiar with book banning in the US, the EU and elsewhere, but in the UK? (Ben is Commissioning Editor of the Telegraph.)

He said, “We are banning books again, and this time it appears to be a consequence of ill-informed hysteria. The Index on Censorship discovered that 28 of the 53 British school librarians they polled had been asked to remove books – many of which were LGBTQ+ titles – from their shelves. It appears that pressure had come from parents and, on some occasions, teachers too. For a society that’s meant to be modern and tolerant, these findings are depressing: the culture wars are failing to subside, and we seem to think nothing of using our children’s education as an ideological battleground.

That battle has been raging in America for several years. In March, the American Library Association reported that 2023 was an all-time peak for such censorship. I imagine that much of the opprobrium launched at titles such as All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M Johnson – the memoir of a young, queer, black activist – was led by Republican-Christian zealots. In Britain, however, the root causes are harder to deduce. Certainly, our national disease of knee-jerk reaction is partly to blame. According to the Index on Censorship, one worker was asked to remove all gay-related content from the school library due to a single complaint about a single book.

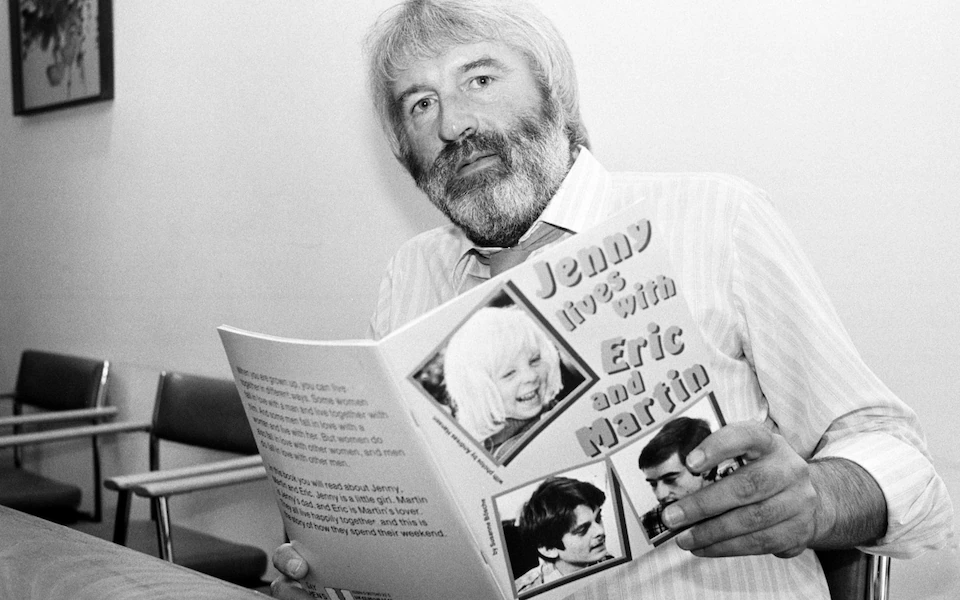

Yet the depressing thing is that we have long been intent on cutting off children from literature and its “dangers”, ignorant of the fact that books are crucial to young people’s development. The current situation in the UK smacks of the dark days of the 1980s, when Section 28 legislated that no local authority could “promote homosexuality”. In the line of fire was a ridiculously innocuous picture book from Denmark called Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, which featured a small girl with two dads, and now looks about as morally corrupting as a Cliff Richard fan convention.

John Clarke, head of Haringey’s Community Information with a copy of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin in September 1986

I sometimes doubt that those who are quick to show their outrage are even concerned about the morals of Britain’s children; it’s more about their own fear of the unfamiliar. Some books represent a world that exists outside their own limited boundaries, which they therefore can’t control. This was the case in the 1980s: Section 28 felt, in part, like the natural product of a society that had failed to come to terms with the Aids epidemic.

But what those who try to ban books consistently fail to realise is that any attempt to arrest social change will ultimately, in a functioning democracy, be doomed. Perhaps in China, where there are edicts against books that fight against communist values – Alice in Wonderland, for example, is banned for its anthropomorphisation of animals – a suppressed book really can stay buried. But in most places, the allure of a title in samizdat will always ensure its longevity.

For censors have always proved to be on the wrong side of history. Those who fettered the genius of James Joyce and banned Ulysses on the grounds of “obscenity now” look like narrow-minded killjoys. As for Lady Chatterley’s Lover by DH Lawrence? For what it’s worth, I’m still not convinced that it’s great literature, but its depiction of sex was a necessary step forward for British society, and the end of its ban a crucial catalyst for making England a more tolerant place.

It’s telling that one of the few authors who refused to defend Lady Chatterley during the 1960 trial at the Old Bailey was Enid Blyton, an author whose work now often looks mean-spirited and bigoted. In fact, Blyton’s books were banned from my own school library in the 1980s – along with Judy Blume’s progressive adolescent novel Forever – which just goes to show how times change.

And yet, although this news from the Index of Censorship is worrying, I still feel hopeful. Curious minds will always seek out good writing, however long it takes them to find it. Book banning may be a global industry – but the freedom to read will always prevail.”