This book, by Lewis Dartnell and subtitled ‘How the Earth Shaped Human History’ caught my attention because it deals with the intersection of science, history and human evolution.

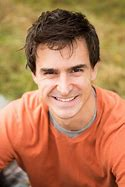

Lewis Dartnell is professor of science communication at the University of Westminster. He has won several awards for his science writing and contributes to the Guardian, The Times and New Scientist. He has also written for television and appeared on the BBC’s Horizon, Sky News, Wonders of the Universe, Stargazing Live and The Sky at Night.

Lewis Dartnell

This book is rich in its recounting of the history of humanity from its evolution in Africa to its spread across the land masses of the world. It then covers the development of the flora and fauna put to different uses by peoples in various parts of the world. This was our early agrarian existence. What we build with, from mud to marble is accounted for in a chapter which describes how these substances originated. Man entered the Iron Age with the smelting of iron ore, but there was also tin, copper, gold and more modern metals. We learn how these metals were formed, where they are found and why. Depending on the places where they settled, people became migrant herdsmen, settled farmers, or traders. The earth is a great ‘wind machine’ whose dependable winds are capable of carrying sailors to particular destinations of interest around the world. This led to exploration and the establishment of global trade. Finally, the discovery of coal and oil led to the industrial revolution, and we learn how these fuels were formed millions of years ago. Along this journey covering millions of years we discover why particular current facts were pre-ordained million of years ago. For example, one can trace the pockets of historic Democratic voting in regions of the American South, to the prevalence of large slave populations to cotton plantations, to particular soil which was left by an ancient receding sea. It is this kind of linkage of human culture and behaviour to geography which provides fascinating insights. Throughout the book there are references to the drifting and collisions of land masses, the resulting mountains and volcanoes, earth’s temperature changes, and the resulting lakes, seas and ice caps.

The book is well worth reading, even if one feels that one has a good sense of the geographic history of the world. It is the relating of the outcomes of that ancient history to specific present-day economic, political and cultural situations, with names, dates and places, which makes it so memorable and interesting.