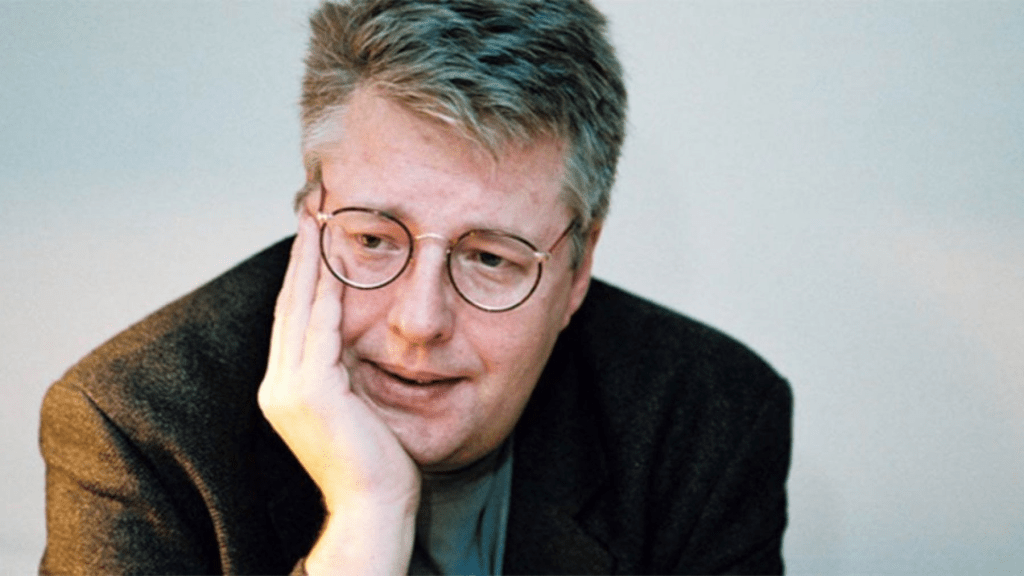

I have now read the third book in this amazing trilogy. You can find reviews of the first two books in the Millennium Trilogy two and four weeks ago. Of the three, I think that the first volume, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, is the best. It has a self-contained plot and is probably the clearest example of Stieg Larsson’s amazing talent for writing thrillers, which include: creating distinctive, memorable characters, building and keeping tension high, designing a plot which captures the reader’s interest, and keeping the reader guessing with surprises at critical junctures in the plot.

Stieg Larsson 1954 – 2004

The plot carries over from the second book in the series. Lisbeth Salander (the heroine) is in the hospital with serious injuries caused by her half-brother, Ronald Niedermann, who has a rare congenital condition which makes him insensitive to pain, and who is on the run with the cash of an outlaw motorcycle club which hired him to kill Lisbeth. Two rooms away in the hospital is Zalachenko, Lisbeth’s father, a former Soviet operative who tortured Lisbeth’s mother, and who was injured by Lisbeth with an axe. Zalachenko is shot to death in his hospital bed by Evert Gullberg, the head of a renegade section of Sapo, the Swedish equivalent of MI6, and who is terminally ill. Zalachenko is killed for fear that he will reveal the existence of the section which protected Zala, and instutionalised Lisbeth with the help of the corrupt psychiatrist, Dr. Peter Teleborian. Gullberg tries to kill Lisbeth, also, but is frustrated by her lawyer Annika Giannini, Mikael Blomkvist’s sister. Gullberg commits suicide. Section operatives murder Gunnar Björk, Zalachenko’s former Säpo handler and Blomkvist’s source of information for an upcoming exposé; the operatives falsify the death as a suicide. Other operatives break into Blomkvist’s apartment and mug Giannini, making off with copies of the classified Säpo file that contains Zalachenko’s identity.

Torsten Edklinth, a Sapo official is informed of the renegade section of Sapo, and begins a clandestine investigation with Monica Figuerola. Blomkvist, secretly arranges to have Lisbeth’s hand-held computer returned to her in the hospital and arranges a mobile phone hot spot to keep her in touch with the outside world. Blomkvist plants misinformation about plans to defend Lisbeth at her trial for the attack on Zala. The section swallows the bait, plants cocaine in Blomkvist’s flat and tries to have him killed.

On the third day of the trial, Blomkvist’s expose is published, causing a media frenzy, and leading to the arrest of section people. Giannini destroys Dr. Peter Teleborian’s credibility, and proves that the section conspired to cancel Lisbeth’s rights. The prosecutor realises that the law is on Lisbeth’s side, withdraws all the charges and the court cancels Lisbeth’s declaration of incompetence.

When she is freed, Lisbeth discovers that she and her twin sister are to share Zala’s estate which includes an abandoned factory. She goes to investigate the property and finds Niedermann hiding there from the police. During a struggle with him, she nails his feet to the floor with a nail gun. She informs the motorcycle gang where Niedermann is and then she informs the police of the resulting chaos. Mikael Blomkvist visits her at her apartment and they reconcile as friends.

This novel is 715 pages long, and, as such, the plot is far more complex than the above summary suggests. It is also richly populated with minor bit-part characters, whom I sometimes had difficulty keeping track of, even though each one had an essential role to play in keeping the story advancing, credibly.

All in all, this is a great story!