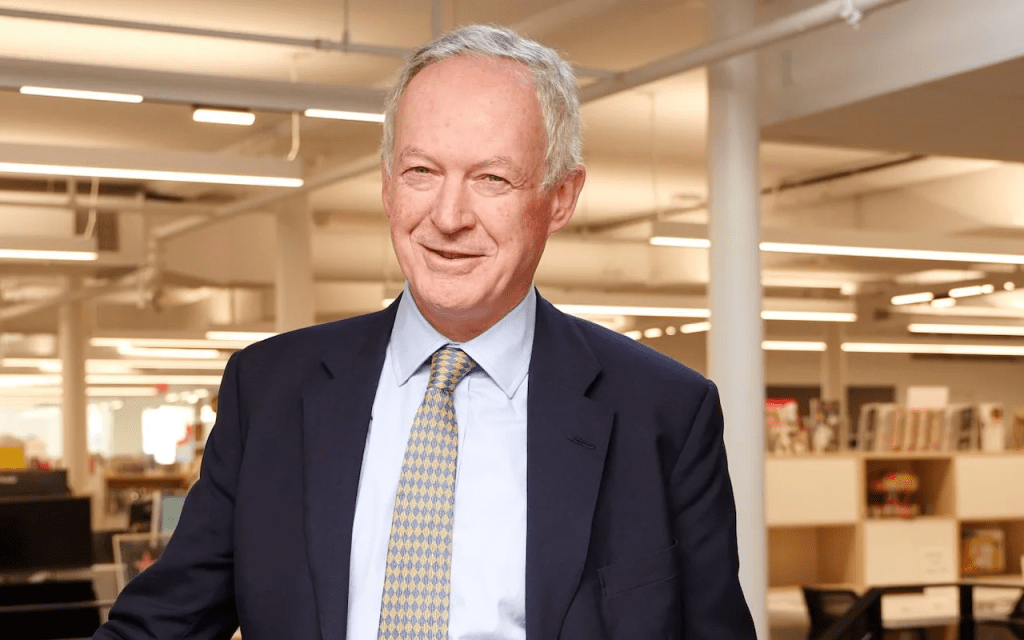

There is an article in today’s Telegraph, by Claire Allfree that explains how Waterstones became a high street success in the face of on-line giants like Amazon. The article focuses on James Daunt, Waterstones CEO. Excerpts are below.

James Daunt

“James Daunt is running between meetings and apologies for having to dash off for a minute before we can begin our chat. While he is gone I squint at the books in his New York office, but alas the Zoom screen is such that I can make out only one title – a biography of the artist Andy Warhol. Quite what a bookshelf would tell you about Daunt though is a moot point: he reads anything and everything.

“I try to knock through a non-fiction book once a week. I’ve just finished The Quiet Coup by Mehrsa Baradaran [about the market failures of American neoliberalism]. I’m reading a book on inflation. Although I’m having a tough time with novels at the moment. I haven’t hit upon something that’s made me feel ‘wow’.”

On second thoughts, perhaps you can deduce from this that Daunt cares very much about the health of new fiction, and that he is deeply concerned about the economy. Neither should be a surprise: Daunt is, after all, the most powerful man in Western bookselling. His footprint has been all over the books we buy and where we buy them ever since he founded the six-store Daunt Books chain, opening its first location on Marylebone High Street in London in 1990 at the age of 26.

Daunt Books’ Marylebone location is one of London’s most famous (and photographed) independent bookshops

In 2011, he was appointed managing director of Waterstones at a time when the chain was in a seeming death loop of forced branch closures and collapsing profits; by 2024 sales had reached £528.4 million, up 17 per cent on the year before, with profits for the same year soaring by £20 million to hit £32.8 million.

In 2019, he became the chief executive of the then floundering US book chain Barnes and Noble (he splits his time between New York and the four-storey Hampstead home he shares with his wife Katy Steward, who works in health care; the couple have two adult daughters) and has overseen an aggressive reboot and expansion, opening 50 stores last year and with another 50 planned for this.

So successful have both companies become that rumours are circulating that Elliott Management, the private equity firm that owns them, plan to float them on the stock exchange. Daunt, though, 61, dismisses such corporate gossip as though it were a bad smell. “These are not my plans at all,” he says, reluctant to disclose any further details for both companies beyond their steady and remorseless growth. “Much of it is pure speculation: one sees that a private equity firm buys a business and assumes that five years on, if the business is doing well, they will sell it. To be honest I lack the imagination to see why one would do things any differently to how we do it now.”

Indeed. The success of Waterstones in the UK is a rare, possibly unique bright spot in a retail market otherwise dominated by the collapse into administration of big brands (Ted Baker is among the latest to be plunged into crisis) and declining profits (Asda announced their worst Christmas since 2015, with sales slumping by more than 5 per cent over the festive period).

“What makes us different is that we stubbornly and tenaciously held on in places where other people have left, so you’ll find us in Grimsby and Middlesborough long after M&S have abandoned these places,” says Daunt. The Waterstones vision is as much ideological as financial. “We have a bookshop in Ayr because it matters that we are there.”

So why is Waterstones soaring and everywhere else floundering? Covid helped: sales rose 73 per cent in 2021-2022 as half of adults doubled their reading time during lockdown and an artfully curated bookshelf became a Zoom must-have accessory. “Most retailers appeal to a relatively small demographic – teenagers, or older men and so forth. We sell to everyone.”

“We have huge advantages,” he argues. “What we sell has a fixed price that we don’t set [book prices are set by the publishers]. So we are remarkably well protected from the consequences of excessive inflation.” Fair enough, but that fixed price is creeping up – it’s now common for literary hardbacks to sell at £22.

“But inflation has been remarkably modest in the UK book market, much less than it is in any other. When I first started selling books in 1990, a paperback was £6. Nor do we sell items that go out of date. Also we are aspirational. Our reach goes beyond the middle class bracket. Many parents want their children to read.”

Daunt’s argument is for a system whereby some communities are taxed more than others. “Sensible structures should be put in place so that Marylebone High Street, which is never going to struggle for occupancy, doesn’t benefit in the way Barrow-in-Furness should.” He doesn’t agree that one answer might be for shops to follow the Waterstones model, which places huge emphasis on the social and aesthetic experience of shopping and targets each shop directly at the needs of its local community.

“The problem is not the shop keeper or the environment. You need to provide an environment that allows them to thrive. And if you give an online retailer a massive incentive to open a huge warehouse, then you are stripping employment from local high streets, which is of huge social and cultural benefit. So don’t shout at the retailer, shout at the warehouse, and this has to be something that starts in Westminster.”

“I was a nice middle-class child who was taken down to Caledonian Road library to pick out my books from a very early age and had my nose in a book from the moment I could read,” he says. “Clearly if one is privileged enough to grow up, in my case with library books, it helps foster a love for reading. We were a nuclear family, although because of my father’s job I was sent to boarding school [Sherborne, in Dorset] which is a way of being educated I suppose. I certainly haven’t subjected my own children [Molly, who works for a security and counter terrorism think tank and is also completing a masters in Middle Eastern Studies at SOAS university, and Eliza, who is studying history at Yale] to that.”

Daunt’s argument is for a system whereby some communities are taxed more than others. “Sensible structures should be put in place so that Marylebone High Street, which is never going to struggle for occupancy, doesn’t benefit in the way Barrow-in-Furness should.” He doesn’t agree that one answer might be for shops to follow the Waterstones model, which places huge emphasis on the social and aesthetic experience of shopping and targets each shop directly at the needs of its local community.

“The problem is not the shop keeper or the environment. You need to provide an environment that allows them to thrive. And if you give an online retailer a massive incentive to open a huge warehouse, then you are stripping employment from local high streets, which is of huge social and cultural benefit. So don’t shout at the retailer, shout at the warehouse, and this has to be something that starts in Westminster.”

In person, Daunt has an air of careful affability. He was born in Islington in 1963. His father, who died in 2023, was the diplomat Timothy Daunt, while his mother, Patricia, brought up James and his two younger sisters – Eleanor, who works for a fragrance company, and Alice, who runs Daunt Travel, a high-end travel business. The house was bookish and he remembers school holidays as being “very intellectual”.

Daunt read history at Cambridge and on leaving joined JP Morgan in 1985, until Katy, at that point his girlfriend, suggested that perhaps he might want to do something else with his life. He set up his first Daunt shop in 1990, taking over an antiquarian bookstore on Marylebone High Street. “Running a business is not at all the tradition of the Daunt family,” he says. “Daunts tend to be either school teachers or public servants, and if you are neither of those things, you tend to join the church.”

There is a vaguely ecclesiastical beauty about the original Daunt shop, with its gorgeous Edwardian gallery and lofty calm. It set the image for the subsequent five Daunt stores that followed, which, given their locations (Holland Park, Hampstead, Belsize Park), retain an air of monied exclusivity, something of which Daunt is well aware.

“There has always been the accusations [with Daunt Books] of being leafy or snobby, and it’s a type that we undoubtedly are: you only have to listen to my accent to hear who I am. But the customer I could always identify was the taxi driver. They are and remain a really good customer base for us because they keep lots of books.”

When he was asked to take over Waterstones by its new owner, the Russian oligarch Alexander Mamut, no one thought he could do it. Amazon was selling books online at aggressive discounts, and there were apocalyptic warnings about the rise of the ebook.

Instead, Daunt set about applying the independent Daunt ethos to Waterstones and, in what seemed a particularly kamikaze move at the time, severing its relationship with publishers. No more in-store promotion displays paid for by publishing houses, a revenue stream that had brought in £27 million a year. And no more three for two discount tables either. He cleared out the management at a loss of 200 jobs and handed buying power to individual stores. “I hate homogeneity,” he says. “The idea is that each time you are creating a bookshop for the local community.”

He has his critics. Some accuse him of being ruthless, an iron fist wrapped in a velvet glove. Is he? “I don’t know if I’m ruthless but I am single-minded as to what a good book shop is. And I don’t compromise on that and I never change my notion of what that is. I will never let people be useless. The key to that, and the bit people have found a bit ruthless, is that I require my bookshops to be run by booksellers. And if you are not interested in books and you don’t read and you don’t care then work somewhere else.”

With such reach and influence can come accusations of excessive curating, even censorship. Daunt bats them away. “We get accused periodically of going all woke, it’s nonsense. Or you get a bit of outrage from some author who says we are no longer stocking their book. And over the years I’ve been accused of not stocking almost every sort of book.”

All the same, does he agree the book industry is increasingly convulsed by the subject of what can and cannot be published? As leading publishers shy away from books with a gender critical perspective, or books with a pro-Israel stance.

“I don’t recognise that. Of course publishers make missteps. They go and clean up Roald Dahl and it’s just absurd. It was a bit of a stupid thing to do. But publishing is such a vigorous landscape that these missteps are soon corrected.”

Do these “missteps” affect what Waterstones select to buy? “Our job is to curate a sensible array of books. And when it comes to books about the Israel and Gaza conflict, we’ve had some real bestsellers such as The Genius of Israel [by Saul Singer and Dan Senor, about Israel’s strength as a nation]. Admittedly, this has been in areas with strong Jewish communities but it was ever thus. We are not dictating to anyone.”

“Yes, sometimes we make mistakes. We made a mistake with Hannah Barnes’ book about the Tavistock Clinic [Time to Think, an exposé of the Tavistock NHS gender clinics which multiple publishers refused to publish; it was eventually published by Swift in 2023] by underestimating how many copies we would need [when it was first published]. So when it sold out, we had to go back to Swift and ask for more copies. It’s a problem for about 10 days. People say ‘you are boycotting it’. We are not boycotting it; we’ve just sold out our initial order.””