Yesterday the Telegraph had an article to this effect written by Hannah Boland, the Retail Editor.

Hannah said, “Across Britain, fewer and fewer people are reading books. The data are plain as day.

The number of children who read outside of school every day has halved over the past two decades, while the number of children who say they enjoy reading in their spare time is down by 36pc.

Among adults, reading numbers are also in freefall. In a YouGov survey last year, two in five people said they had not read or listened to a book in the past year – compared with around a quarter of adults in 2001.

For Waterstones, figures such as these would be expected to raise alarm bells. With the high street in crisis, you would think the decline of reading would put businesses such as Waterstones next in line to face the chop.

Yet the mood is anything but sombre at Britain’s biggest bookseller. In fact, Waterstones’ owners are so confident in the business that they are gearing up for a multibillion-pound stock market listing, with a float expected as soon as this summer.

This month, it emerged that Elliott Advisors, the company’s owner, had lined up advisers at Rothschild to work on the process.

The private equity group is preparing to list both Waterstones and its US cousin Barnes & Noble together as one business.

In a sign of just how well Waterstones appears to be doing, Elliott is understood to be leaning towards the London Stock Exchange for a debut of the combined company.

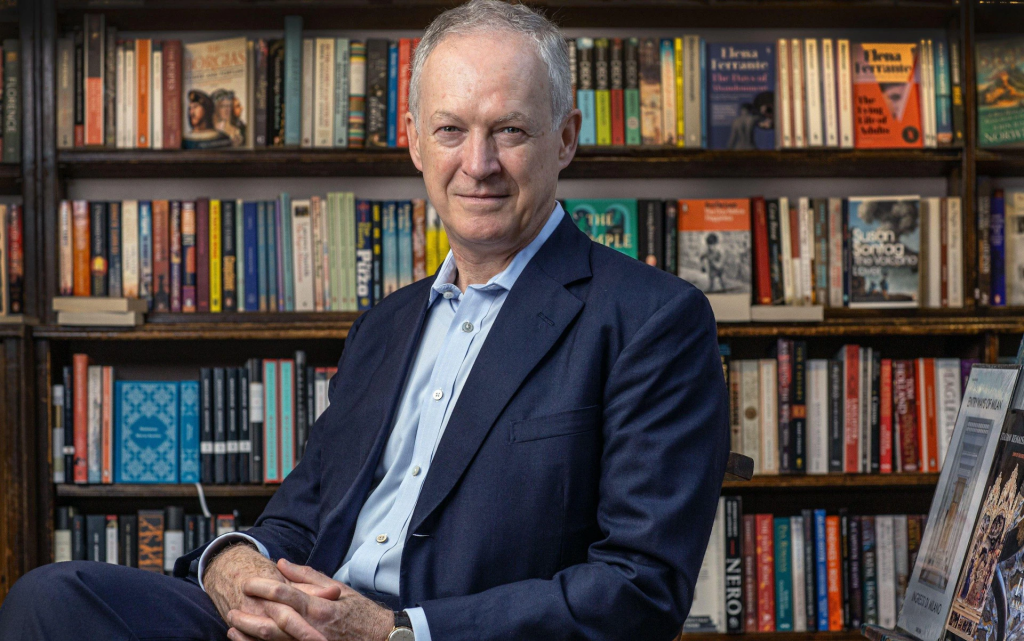

James Daunt, the bookseller’s lauded chief executive who also runs Barnes & Noble, is himself a Briton.

Daunt, who runs both booksellers, described 2025 as a “fantastic year for us”, with both the US and UK businesses expanding into new areas.

Barnes & Noble opened 67 new stores while Waterstone is adding around 10 new shops a year, even though expansion is harder given it is so well-established.

“Stories of declines in reading evidently do not correlate to book buying,” he says. “Publishers and independent booksellers, as well as ourselves, are all doing well in both the US and the UK.”

The figures back him up. The number of independent booksellers across the UK rose slightly last year, even as the high street was struck by a series of retail collapses and store closures.

Between them, Barnes & Noble and Waterstones made a profit of $400m (£300m) last year, with sales standing at $3bn.

That is despite Barnes & Noble facing the same problem with declining reading numbers as Waterstones. A study by the University of Florida in August found that the number of Americans reading for pleasure had plunged by 40pc over the past 20 years.

Official accounts show that Waterstones’ sales rose to £565.6m for the 12 months to May 3, compared with £528.4m a year earlier, according to documents published on Companies House this week. It made pre-tax profits of £40m for the year.

Barnes & Noble opened 67 new stores while Waterstone is adding around 10 new shops a year, even though expansion is harder given it is so well-established.

Waterstones recently said it had been boosted by growing demand for “romantasy” novels – known colloquially as fairy porn.

These fantastical tales of heroines being swept off their feet by knights and wizards have gained huge numbers of fans among British women.

Sarah J Maas, author of romantasy novel A Court of Thorns and Roses, has sold more than 75 million copies of her books globally. Publisher Bloomsbury said demand for Maas’s books helped it to the highest first-half sales and earnings in its history last year.

Elliott is understood to be planning to remain as the biggest shareholder in the combined bookselling business for some time following the market debut, which may give new investors more confidence in its future.

One banking source suggested now was as good a time as any for Elliott to kick off the process of listing Waterstones on the stock market and realising some return on its investment.

“Everything is a bit s–t,” they said. “But that’s not going to change anytime soon and there have been so few returns back on private equity that if they can, they probably should.”

For Daunt, his focus continues to be on the day-to-day. Over the past week, he has been travelling down the west coast of the US to visit Barnes & Noble shops. Despite falling reader numbers across both the US and UK, Daunt says stores are thriving.

“Bookselling is presently vibrant,” he says.

Soon he will find out if investors agree.”