Matt’s cartoon from last week’s Daily Telegraph!

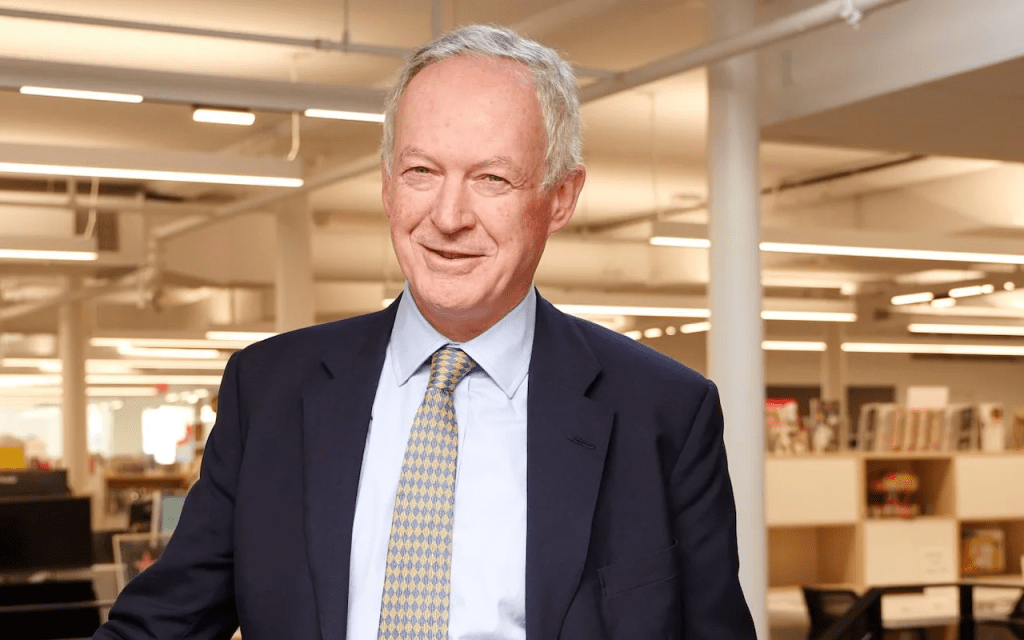

Yesterday’s Telegraph has an article by Philip Johnston about the dangers of giving AI companies (particularly American ones) a free hand in training their artificial intelligence.

Philip Johnston has been with the Daily Telegraph for more than 20 years. He is currently assistant editor and leader writer and was previously home affairs editor and chief political correspondent.

Philip Johnston

He wrote, “Labour is planning to undermine copyright laws. The only winners will be the Silicon Valley tech bros.

Have you read any good books by Franklin Chase recently? Who on earth is he, you may well ask. I was on the Amazon site looking to pre-order Ungovernable, the diaries of Simon Hart, the former government chief whip, only to see another copy of almost the same book was already on Kindle. Moreover, it was “available instantly”, unlike Mr Hart’s which does not come out until the end of this week.

Only it wasn’t the same book, but an AI generated imitation with just 46 pages for £8.99. I downloaded it to find what might charitably be called a pile of old rubbish. “Politics is not for the weak,” its prologue begins. “It resembles a battlefield where alliances shift unpredictably, loyalty is often quickly exhausted and the difference between success and failure is extremely narrow. Few have navigated this perilous journey … Simon Hart is one of those exceptional individuals.”

Chapter one opens with the “August sun casting long shadows across the undulating hills of the Cotswolds” where a six-year-old Hart “dashed through the fields, his laughter carried by the breeze”. At least I hope this isn’t the real book. Who has got my wasted £8.99 I have no idea.

I called up Simon, an old acquaintance, and pointed out that this book by one Franklin Chase was basically pretending to be his and might be bought by an unwary would-be reader who had enjoyed the newspaper extracts of the real McCoy last week. He had recently been alerted to this but was told by his publishers that nothing could be done about it. “It is one of those those things in the new AI world” they said.

Indeed, it turns out that Mr Chase is quite a prolific mimic of other books. Among his recent publications are the memoirs of the actress Tuppence Middleton – Rising Through the Storm: A Journey of Fear, Fame and Fierce Resilience. Or the footballer Duncan Ferguson – From Prison Walls to Premier League Triumph. Or Robert Dessaix, the Australian author, Abandoned at Birth, Shaped by Love.

Each of these authors has a book coming out which these titles purport to emulate, all with the real name far larger than the enigmatic and indefatigable Chase, who is clearly an AI bot. These rip-offs are examples of the way generative AI is able to plunder massive amounts of data to create an almost instant book.

Since they are not plagiarised, they are strictly not a breach of copyright but doubtless they use information from some sources that should be protected. Amazon says it takes these fakes down if complaints are made but so many are appearing it is hard to keep up. Indeed, there is already another Simon Hart lookalike on the website: The Untold Story of a Modern Conservative by one Maeve Sterling, who also managed to publish a biography of Louis B Mayer this month.

The Labour Government now proposes to blunder into this brave new world by making it easier for tech giants to “mine” for creative material to feed into the voracious maws of their AI monsters. A 10-week consultation period into plans to remove copyright protections enjoyed by authors, musicians and others so that their work can be plundered to “train” their algorithms ended on February 24. This would be done by way of what is known as the text and data mining (TDM) exemption that currently applies to non-commercial research and would be extended to creative works still under copyright.

The work of British writers, composers and artists could be purloined allowing AI companies to profit from them and, in many cases, not repay the creator. The AI creations would then get IP protection despite having compromised the intellectual property of others. It is astonishing that a British government would contemplate this and yet this is the preferred option in the consultation paper.

Ministers are even planning to block an attempt in the House of Lords to preserve copyright laws by amending the Data (Use and Access) Bill now before Parliament. Baroness Kidron, a film-maker and crossbench peer behind the amendments, said this would be a “travesty”. She added: “The Government has just shown its colours again. It wants to make the UK an AI hub of America and they’re sacrificing the creative industries to do it.”

The Daily Telegraph in common with other newspapers has issued an eleventh-hour plea to ministers to drop the idea. If anything, they should be strengthening copyright against this wholly new and sinister attack on creative material.

Some big stars have joined the hue and cry. Brian May, the Queen guitarist, fears the industrial scale theft of other people’s talent by the AI behemoths cannot be stopped. Simon Cowell, the music producer, said the artistic livelihoods of many risk being wiped out. A letter signed by scores of artists said the Government’s approach “would smash a hole in the moral right of creators to present their work as they wish”, jeopardising the country’s reputation as a beacon of creativity.

The idea that a Labour government is bending over backwards to fill the coffers of Meta, Google and Elon Musk in this way is frankly baffling. So, too, was the Government’s refusal along with the Americans to sign a recent communiqué in Paris about controlling the growth of AI.

Sir Keir Starmer, who is to meet Donald Trump on Thursday, may have calculated that it would be better to be seen to support the AI Wild West that the new White House is happy to see and hope we get a slice of the action.

In the absence of anything else, Labour sees AI as the key to unlocking growth. Supporters say copyright restrictions get in the way of AI’s development and leave the UK struggling to catch up with America and China. Meanwhile, the people who invented AI are terrified about what it might do next.

Of course, the theft of creative material is hardly new. When a Christmas Carol was published in December 1843, knock-offs were on the streets within days claiming to be by Dickens. When a pirated version appeared in Peter Parley’s Illuminated Magazine the author sought an injunction against the publication.

He won but the magazine declared bankruptcy, leaving Dickens with costs of £700. It was thefts like these which necessitated copyright laws. It would be grotesque were Labour now to preside over their demise just to ingratiate themselves with J D Vance.”

Hows true! We’ll have to write to our MPs!

The Guardian’s website has an article by Ed Pilkington, dated 13 February 2025 under the title ‘Pentagon schools suspend library books for ‘compliance review’ under Trump orders’.

Ed Pilkington is Chief Reporter for The Guardian in the US

He wrote: “Tens of thousands of American children studying in Pentagon schools serving US military families have had all access to library books suspended for a week while officials conduct a “compliance review” under Donald Trump’s crackdown on DEI and gender equality.

The Department of Defense circulated a memo to parents on Monday that said that it was examining library books “potentially related to gender ideology or discriminatory equity ideology topics”. The memo, which has been obtained by the Guardian, said that a “small number of items” had been identified and were being kept for “further review”.

Books deemed to be in possible violation of the president’s executive orders targeting transgender people and so-called “radical indoctrination” of schoolchildren have been removed from library shelves. The memo states that the titles have been relocated “to the professional collection for evaluation with access limited to professional staff”.

The censorship of library books in defense department schools provoked a furious response from Jamie Raskin, the ranking Democrat on the House judiciary committee. He slammed the practice as “naked content and viewpoint censorship of books”, during a hearing on the “censorship-industrial complex” on Wednesday.

Raskin invited other members of Congress to join him in “denouncing the purge of books, the stripping of books from the Department of Defense libraries or any other public libraries in America”.

The purge of library books will affect up to 67,000 children being taught in Pentagon schools worldwide. The Guardian understands that all 160 schools, located in seven US states and 11 countries, are subject to the censorship.

The Guardian has obtained a list of books that have been caught up in the blanket evaluation. They include No Truth Without Ruth, a picture book for four-to-eight-year-olds about the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second woman to sit on the US supreme court.

The book, by the award-winning writer Kathleen Krull, describes the sexist discrimination Ginsburg had to overcome in her rise to becoming a supreme court justice.

Other titles that have been caught up in the review include a book by the American Oscar-winning actor Julianne Moore. Freckleface Strawberry, also for four-to-eight year olds, features a young girl coming to terms with her freckles.

The Guardian invited the defense department to comment on the review of these and other titles, but a spokesperson did not refer to individual titles.

In a statement, the Department of Defense education activity confirmed that it was carrying out a review of library books as part of an examination of all “instructional resources”. The purpose was to ensure that Pentagon schools were aligned to Trump’s recent executive orders, Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling.”

All book banns, except those which include books advocating violence, are to my mind a violation of the concept of Freedom of Speech. In their enthusiasm for cancelling DEI and gender self-identity, the Trump administration has gone too far.

There is an article in the February 6 issue of the Telegraph by Jake Kerridge which exposes a publishing process which is not well known and could mean ‘the end of original thought’.

Jake Kerridge is a UK-based journalist who specializes in writing about books and literature. With a keen eye for detail and a passion for storytelling, he has established himself as one of the leading books journalists in the country. As a regular contributor to The Telegraph, Kerridge’s work reaches a wide audience of book enthusiasts and industry professionals alike, making him a go-to source for the latest news, reviews, and insights into the world of literature.

Jake Kerridge

Jake says, “Reader demand for the world-conquering genre of “romantasy” (romance/fantasy) has grown so voracious that publishers are struggling to keep up the supply. That’s the conclusion I drew recently when I stumbled on an advert asking for “unpublished Young-Adult fantasy romance authors to audition for the chance to write a YA novel”.

One burden the successful applicant would be relieved of was thinking of a plot: this was already outlined in the advert. “Trapped on an enchanted cross-kingdom train to her wedding, a fiery princess works alongside her infuriatingly attractive new bodyguard to expose a killer onboard.”

Working Partners, the company that placed the advert, describes itself not as a publisher but as a “book packager”. The phrase might conjure up visions of people wielding bubble wrap in a warehouse, but for some decades now these organisations have played a vital role in the publishing ecosystem – though they tend to stay out of the limelight.

Book packaging companies vary in scale from conglomerate to cottage industry, but they usually comprise a permanent editorial staff and various freelance writers. The majority of them deal in fiction and non-fiction for children and young adults, and they are collaborative affairs, with the writers fleshing out ideas given to them.

There are generally two ways for a packaging company to become successful at placing books with publishers: produce, through the alchemy of collaboration, brilliant ideas; or get your staff to churn out books far more quickly than the publishers could do themselves in-house. If it sounds like literature on the factory farm model, packagers seem reluctant to dispel such ideas by shedding light on themselves.

“I think part of the reason book packagers get a bad rap is that there is a secrecy around the process, so it feels all a bit smoke and mirrors,” says Jasmine Richards, who founded the packager Storymix in 2019. “For example, celebrity fiction titles are often produced by packagers and traditionally that’s not been publicly acknowledged, although publishers are now getting better at crediting ghostwriters.

The Carnegie-nominated Fablehouse by EL Norry is one of Storymix’s big successes

“Personally I’m really proud to be a packager and to say out loud that we find talent and support it. So many writers get their first break with a book packager: you come and get paid to work on a project, build up your writing muscle and learn about the industry. Then maybe go on to sell your own project.”

Nevertheless, publishers remain wary of being publicly associated with the packaging model. In the US the romantasy community has been rocked this month by a lawsuit alleging plagiarism against Tracy Wolff, author of top-selling girl-meets-vampire yarns such as Crave.

In mounting her defence, Wolff’s lawyer revealed that her publisher, Liz Pelletier, was heavily involved in the writing of Crave, “a collaborative project with Pelletier providing to Wolff … the main plot, location, characters, and scenes, and actively participating in the editing and writing process.”

Pelletier, who runs the publishing company Entangled, has told The New Yorker that she commissioned Wolff to write Crave – “the fastest writer I’ve ever worked with” – to fill a gap in her publishing schedule when another author failed to deliver a book. Wolff produced the first draft in two months.

Commentators have dubbed Entangled a book packager in all but name, something Pelletier has denied almost as strenuously as the plagiarism accusations. If a conventional publisher gets a reputation for following the packager model in-house, they may struggle ever to woo big-name authors to their stable.

However, the romantasy genre does perhaps seem more suited to the packager model than to authors who want to express themselves artistically or come up with original ideas. Romantasy novels repeat tropes ad infinitum – love across class (or species) divides, love triangles, enemies becoming lovers – and the sales figures suggest that the more formulaic the book, the better romantasy readers like it.

With publishers able to see what tropes are trending on BookTok – #morallygreymen and #daggertothethroat are popular hashtags for romantasy readers – they are reportedly shaping books accordingly. (The New Yorker reports that Pelletier told another author: “the problem with traditional publishing is that they just let writers write whatever they want, and they don’t even think about what the TikTok hashtag is going to be”. Pelletier has said that she does not recall this conversation.)

As one fantasy novelist (who asked not to be named) put it to me, publishers do seem to be following the packager model more. “It is expensive to build up an author’s career over time, especially if you invest in them and then they turn out to be, say, Neil Gaiman. There’s a sense among publishers that the TikTok generation responds more to individual books than authors.

“It’s cheaper for publishers to hire packagers, or work like packagers, and tailor a book to its potential readership. One outcome of that is books become not just formulaic – they’re indistinguishable.” (I asked the big five UK publishers whether they were increasingly using packaging companies when it came to fiction; none responded to my request for comment).

If it’s easy to see why publishers commission work from packagers, what’s in it for the writers who toil away for them? Certainly not the money, says Honor Head, a veteran writer of children’s non-fiction for numerous book packagers. “It’s really badly paid. Usually if you work in packaging you don’t get a royalty, you get a flat fee. And if the publisher comes back and says ‘I don’t like what you’ve written’, you don’t get any more money for doing it again. But I love writing for children, and I’ve got to a stage of my life now where I don’t need to make as much money.”

There is a suggestion of the salt mines about working for book packagers. In 2010 the packager Full Fathom Five, founded by the author James Frey, was denounced by the New York Times as a “fiction factory”, with creative writing students or graduates writing up Frey’s story concepts for the unprincely sum of $250 per novel.

In China, the phenomenal popularity of wuxianwen, a type of serial fiction published straight to smartphones and tablets, is maintained by the equivalent of packagers: editors map out story arcs and farm various portions of the story out to different writers, each of whom is expected to produce 10,000 words daily.

Head recalls that when she started her own packager some years ago, she and her partner “were working dawn to dusk seven days a week”. Life is more relaxed now she freelances writing children’s non-fiction for other packagers, although her rate is impressive: “I would say the longest I’ve spent on a single book – researching, writing, and then doing any checks – would be a week. It depends on the age group, but I can get a book done in half a day.” She enjoys the discipline of writing to guidelines, although it can be frustrating working on, say, a book on dinosaurs for the US market and being obliged not to write anything that contradicts creationist theory.

Storymix founder Jasmine Richards favours an organic approach to packaging, devising ideas for YA and children’s fiction with her writers and then approaching publishers rather than being commissioned. Her aim is “to put kids and teens of colour at the heart of the action”.

“When my son was about five we were in the bookshop and I couldn’t find a single book on the shelf that featured a character that looked like him. As an editor and author I thought: what’s the best way to change the look of that shelf as quickly as possible? As an author I can write one book a year, but if I start my own book packager I could get several books on that shelf.”

Among Storymix’s big successes is the Carnegie-nominated Fablehouse by EL Norry, which was sold by Richards to Harry Potter publisher Bloomsbury.

“My job is often to matchmake the right idea with the right writer,” says Richards. “I had thought about a fantasy novel with a setting based on Holnicote House, which in the 1940s and ’50s took care of the children who came from relationships between African-American GIs and white British women. I knew exactly the writer I’d love to work on this project: Emma Norry, because I knew she had grown up in care and was of mixed-race heritage. I gave her a storyline, and I remember when she sent me the first chapter, I let the dinner burn in the oven while I read it. That’s a good example of how this method can unlock something amazing.”

Factories undermining the traditional autonomy of the author, or crucibles of collaborative magic? Whichever way you look at them, it’s clear that, despite most of us being unaware of their existence, without packagers the publishing landscape would look very different.”

This is a segment of the publishing market in which most of us would have no interest, either as writers or readers, but it clearly exists to serve the interests of some (perhaps a large group) of readers.

There is an intriguing article by Carter Wilson on the Writer’s Digest website on how and why to use an unreliable narrator in fiction – dated 29 January 2025.

Carter Wilson is the USA Today bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed, standalone psychological thrillers. He is an ITW Thriller Award finalist, a five-time winner of the Colorado Book Award, and his works have been optioned for television and film. Carter lives outside of Boulder, Colorado.

Carter Wilson

Carter says, “Crafting a convincing unreliable narrator might be one of the most difficult things a thriller writer does. Of course, a narrator doesn’t have to be unreliable. A perfectly dependable narrator is often just what the thriller reader needs. A voice of reason and stability thrust in the midst of chaos. Sometimes we want that level-headed hero to guide us through those dangerous waters.

But sometimes…

Sometimes we, as readers, don’t want stability. Sometimes, in the middle of that chaos, we don’t want to believe anyone, including the voice that’s at the helm. Occasionally the fun is figuring out who to trust, if there’s anyone to trust at all. The best thrillers are often the ones in which the protagonist is not only fooling the reader, but themselves as well.

I specialize in writing unreliable narrators, and when I try to dissect why exactly that is, I can think of a few reasons. There are likely many more, but that may take thousands of dollars of therapy to tease out. But top-of-mind, these reasons stand out.

I mean that with 82% sincerity. I don’t outline, and usually I only have the vaguest notion of a plot idea, or sometimes I only know the first chapter. My stories unfold to me one day at a time, which means my narrator is just as lost as I am. I’m writing from my subconscious, which lends itself to a labyrinth of twists and turns, many of which the narrator has created for themselves. Simply put, my narrator is unreliable because the author is unreliable.

If one really considers what makes a narrator unreliable, a few choice adjectives pop up. Deceitful, delusional. In denial. Okay, do those words not describe all of us, at least in some part of our lives? Unreliable is honest. What’s not honest is a hero who can do no wrong, always has the answers, and is always willing to save others before themselves. Is this an admirable protagonist? Yes, of course. But it makes for a helluva boring thriller.

I typically write from a first-person, present-tense point of view. That means I’m seeing the world through my narrator’s eyes, moment by moment. This makes writing an unreliable narrator most effective, because the reader experiences the thoughts and actions as the protagonist does, and offers a fractured, almost stream-of-consciousness narration. What’s more unreliable in our daily lives than our swirling thoughts, our sudden fears, our whimsical and wholly unattainable daydreaming?

Writing an unreliable narrator brings me great joy, because I know readers will be lured into thinking one way until suddenly they’re forced to face an altogether different reality. But it’s also a tricky way to write, and the writer has to strike the perfect balance between believability and deus ex machina. An unreliable narrator shouldn’t be approached as a literary device; rather, a narrator’s unreliability should be an organic result of who they are and the decisions they make.

No author should set out and think to themselves, “I’m going to write an unreliable narrator.” That leads to clumsy and shoehorned writing. Rather, the author should pen the novel as it occurs to them from the subconscious, and only after reading the first draft should they themselves realize their protagonist is not to be trusted. The best writing comes from ephemeral, naturally occurring thoughts rooted in decades of life experience and keen observation. The worst writing comes from market-conscious intentions.

In my newest release, Tell Me What You Did, my protagonist Poe Webb’s unreliability is less a device than a simple fact of life. She lies to the audience because she lies to herself. Poe committed a horrible crime in her past, and though that experience has largely informed who she is in the story, she’s suppressed the memory enough that she struggles to even admit to herself what she did until events force her to reckon with her past actions. Her unreliability is, at its core, human.

The final key in writing an unreliable narrator is to avoid coyness. Too many times an author hints over and over that their protagonist is not to be trusted, building up an anticipation that’s so great the payoff never quite satisfies. Rather, the best unreliable narrators are those who never wink at the camera, and when they look into the mirror they’re just as convinced as we are that the person in front of them is telling the truth.

Like I coach all my students, write from the heart, from the soul, from instinct, from the subconscious. From that perspective, an unreliable narrator is not a trick but rather a fully formed individual who is convinced they are doing the right thing, despite all evidence to the contrary. This results in a hero—or anti-hero—who is, above all else, uniquely flawed and morally gray. Just like all of us.”

There is an article in today’s Telegraph, by Claire Allfree that explains how Waterstones became a high street success in the face of on-line giants like Amazon. The article focuses on James Daunt, Waterstones CEO. Excerpts are below.

James Daunt

“James Daunt is running between meetings and apologies for having to dash off for a minute before we can begin our chat. While he is gone I squint at the books in his New York office, but alas the Zoom screen is such that I can make out only one title – a biography of the artist Andy Warhol. Quite what a bookshelf would tell you about Daunt though is a moot point: he reads anything and everything.

“I try to knock through a non-fiction book once a week. I’ve just finished The Quiet Coup by Mehrsa Baradaran [about the market failures of American neoliberalism]. I’m reading a book on inflation. Although I’m having a tough time with novels at the moment. I haven’t hit upon something that’s made me feel ‘wow’.”

On second thoughts, perhaps you can deduce from this that Daunt cares very much about the health of new fiction, and that he is deeply concerned about the economy. Neither should be a surprise: Daunt is, after all, the most powerful man in Western bookselling. His footprint has been all over the books we buy and where we buy them ever since he founded the six-store Daunt Books chain, opening its first location on Marylebone High Street in London in 1990 at the age of 26.

Daunt Books’ Marylebone location is one of London’s most famous (and photographed) independent bookshops

In 2011, he was appointed managing director of Waterstones at a time when the chain was in a seeming death loop of forced branch closures and collapsing profits; by 2024 sales had reached £528.4 million, up 17 per cent on the year before, with profits for the same year soaring by £20 million to hit £32.8 million.

In 2019, he became the chief executive of the then floundering US book chain Barnes and Noble (he splits his time between New York and the four-storey Hampstead home he shares with his wife Katy Steward, who works in health care; the couple have two adult daughters) and has overseen an aggressive reboot and expansion, opening 50 stores last year and with another 50 planned for this.

So successful have both companies become that rumours are circulating that Elliott Management, the private equity firm that owns them, plan to float them on the stock exchange. Daunt, though, 61, dismisses such corporate gossip as though it were a bad smell. “These are not my plans at all,” he says, reluctant to disclose any further details for both companies beyond their steady and remorseless growth. “Much of it is pure speculation: one sees that a private equity firm buys a business and assumes that five years on, if the business is doing well, they will sell it. To be honest I lack the imagination to see why one would do things any differently to how we do it now.”

Indeed. The success of Waterstones in the UK is a rare, possibly unique bright spot in a retail market otherwise dominated by the collapse into administration of big brands (Ted Baker is among the latest to be plunged into crisis) and declining profits (Asda announced their worst Christmas since 2015, with sales slumping by more than 5 per cent over the festive period).

“What makes us different is that we stubbornly and tenaciously held on in places where other people have left, so you’ll find us in Grimsby and Middlesborough long after M&S have abandoned these places,” says Daunt. The Waterstones vision is as much ideological as financial. “We have a bookshop in Ayr because it matters that we are there.”

So why is Waterstones soaring and everywhere else floundering? Covid helped: sales rose 73 per cent in 2021-2022 as half of adults doubled their reading time during lockdown and an artfully curated bookshelf became a Zoom must-have accessory. “Most retailers appeal to a relatively small demographic – teenagers, or older men and so forth. We sell to everyone.”

“We have huge advantages,” he argues. “What we sell has a fixed price that we don’t set [book prices are set by the publishers]. So we are remarkably well protected from the consequences of excessive inflation.” Fair enough, but that fixed price is creeping up – it’s now common for literary hardbacks to sell at £22.

“But inflation has been remarkably modest in the UK book market, much less than it is in any other. When I first started selling books in 1990, a paperback was £6. Nor do we sell items that go out of date. Also we are aspirational. Our reach goes beyond the middle class bracket. Many parents want their children to read.”

Daunt’s argument is for a system whereby some communities are taxed more than others. “Sensible structures should be put in place so that Marylebone High Street, which is never going to struggle for occupancy, doesn’t benefit in the way Barrow-in-Furness should.” He doesn’t agree that one answer might be for shops to follow the Waterstones model, which places huge emphasis on the social and aesthetic experience of shopping and targets each shop directly at the needs of its local community.

“The problem is not the shop keeper or the environment. You need to provide an environment that allows them to thrive. And if you give an online retailer a massive incentive to open a huge warehouse, then you are stripping employment from local high streets, which is of huge social and cultural benefit. So don’t shout at the retailer, shout at the warehouse, and this has to be something that starts in Westminster.”

“I was a nice middle-class child who was taken down to Caledonian Road library to pick out my books from a very early age and had my nose in a book from the moment I could read,” he says. “Clearly if one is privileged enough to grow up, in my case with library books, it helps foster a love for reading. We were a nuclear family, although because of my father’s job I was sent to boarding school [Sherborne, in Dorset] which is a way of being educated I suppose. I certainly haven’t subjected my own children [Molly, who works for a security and counter terrorism think tank and is also completing a masters in Middle Eastern Studies at SOAS university, and Eliza, who is studying history at Yale] to that.”

Daunt’s argument is for a system whereby some communities are taxed more than others. “Sensible structures should be put in place so that Marylebone High Street, which is never going to struggle for occupancy, doesn’t benefit in the way Barrow-in-Furness should.” He doesn’t agree that one answer might be for shops to follow the Waterstones model, which places huge emphasis on the social and aesthetic experience of shopping and targets each shop directly at the needs of its local community.

“The problem is not the shop keeper or the environment. You need to provide an environment that allows them to thrive. And if you give an online retailer a massive incentive to open a huge warehouse, then you are stripping employment from local high streets, which is of huge social and cultural benefit. So don’t shout at the retailer, shout at the warehouse, and this has to be something that starts in Westminster.”

In person, Daunt has an air of careful affability. He was born in Islington in 1963. His father, who died in 2023, was the diplomat Timothy Daunt, while his mother, Patricia, brought up James and his two younger sisters – Eleanor, who works for a fragrance company, and Alice, who runs Daunt Travel, a high-end travel business. The house was bookish and he remembers school holidays as being “very intellectual”.

Daunt read history at Cambridge and on leaving joined JP Morgan in 1985, until Katy, at that point his girlfriend, suggested that perhaps he might want to do something else with his life. He set up his first Daunt shop in 1990, taking over an antiquarian bookstore on Marylebone High Street. “Running a business is not at all the tradition of the Daunt family,” he says. “Daunts tend to be either school teachers or public servants, and if you are neither of those things, you tend to join the church.”

There is a vaguely ecclesiastical beauty about the original Daunt shop, with its gorgeous Edwardian gallery and lofty calm. It set the image for the subsequent five Daunt stores that followed, which, given their locations (Holland Park, Hampstead, Belsize Park), retain an air of monied exclusivity, something of which Daunt is well aware.

“There has always been the accusations [with Daunt Books] of being leafy or snobby, and it’s a type that we undoubtedly are: you only have to listen to my accent to hear who I am. But the customer I could always identify was the taxi driver. They are and remain a really good customer base for us because they keep lots of books.”

When he was asked to take over Waterstones by its new owner, the Russian oligarch Alexander Mamut, no one thought he could do it. Amazon was selling books online at aggressive discounts, and there were apocalyptic warnings about the rise of the ebook.

Instead, Daunt set about applying the independent Daunt ethos to Waterstones and, in what seemed a particularly kamikaze move at the time, severing its relationship with publishers. No more in-store promotion displays paid for by publishing houses, a revenue stream that had brought in £27 million a year. And no more three for two discount tables either. He cleared out the management at a loss of 200 jobs and handed buying power to individual stores. “I hate homogeneity,” he says. “The idea is that each time you are creating a bookshop for the local community.”

He has his critics. Some accuse him of being ruthless, an iron fist wrapped in a velvet glove. Is he? “I don’t know if I’m ruthless but I am single-minded as to what a good book shop is. And I don’t compromise on that and I never change my notion of what that is. I will never let people be useless. The key to that, and the bit people have found a bit ruthless, is that I require my bookshops to be run by booksellers. And if you are not interested in books and you don’t read and you don’t care then work somewhere else.”

With such reach and influence can come accusations of excessive curating, even censorship. Daunt bats them away. “We get accused periodically of going all woke, it’s nonsense. Or you get a bit of outrage from some author who says we are no longer stocking their book. And over the years I’ve been accused of not stocking almost every sort of book.”

All the same, does he agree the book industry is increasingly convulsed by the subject of what can and cannot be published? As leading publishers shy away from books with a gender critical perspective, or books with a pro-Israel stance.

“I don’t recognise that. Of course publishers make missteps. They go and clean up Roald Dahl and it’s just absurd. It was a bit of a stupid thing to do. But publishing is such a vigorous landscape that these missteps are soon corrected.”

Do these “missteps” affect what Waterstones select to buy? “Our job is to curate a sensible array of books. And when it comes to books about the Israel and Gaza conflict, we’ve had some real bestsellers such as The Genius of Israel [by Saul Singer and Dan Senor, about Israel’s strength as a nation]. Admittedly, this has been in areas with strong Jewish communities but it was ever thus. We are not dictating to anyone.”

“Yes, sometimes we make mistakes. We made a mistake with Hannah Barnes’ book about the Tavistock Clinic [Time to Think, an exposé of the Tavistock NHS gender clinics which multiple publishers refused to publish; it was eventually published by Swift in 2023] by underestimating how many copies we would need [when it was first published]. So when it sold out, we had to go back to Swift and ask for more copies. It’s a problem for about 10 days. People say ‘you are boycotting it’. We are not boycotting it; we’ve just sold out our initial order.””

Harry Bingham, of Jericho Writers, sent out an excellent, comprehensive email a week ago last Friday about how to describe the emotions of a character without TELLING.

He said, “Today I want to give a more comprehensive, more fully ordered list of options.

Honestly, I doubt if many of you will want to pin those options to the wall and pick from them, menu-style, as you write. But having these things in your awareness is at least likely to loosen your attachment to the clench-n-quake school of writing.

Let’s say that we have our character – Talia, 33, single. She’s the keeper of Egyptian antiquities at a major London museum, and the antiquities keep going missing. She’s also rather fond of Daniel, 35, a shaggy-haired archaeologist. Our scene? Hmm. Talia and a colleague (Asha, 44) are working late. They hear strange noises from the vault. They go to investigate and find some recent finds, Egyptian statuary, have been unaccountably moved. In the course of the scene, Asha tells Talia that she fancies Daniel … and thinks he fancies her back.

In the course of the scene, Talia feels curious about the noises in the vault, feels surprise and fear when she finds the statues have been moved. And feels jealousy and uncertainty when Asha speaks of her feelings for Daniel.

We need to find ways to express Talia’s feelings in the story.

Here’s one way:

Direct statements of emotion

Talia felt a surge of jealousy, that almost amounted to anger.

Bingo. Why not? That’s what she feels, so why not say it? No reason at all. Some writers will panic that they’re telling not showing, and they’ve read somewhere that they shouldn’t do that (at all, ever), so they’ll avoid these direct statements. But why? They work. They’re useful. They help the reader.

More complicated but still direct statements

Somewhere, she felt a shadow-self detach from her real one, a shadow self that wanted to claw Asha’s face, pull her hair, draw blood, cause pain.

That’s still saying “Talia felt X”, we’ve just inserted a more complicated statement into the hole marked X, but it still works. And that dab of exotic imagery gives the whole thing a novelly feel, so we’re good, right? Even though technically, we’re still telling not showing.

Physical statements: inner report

Talia felt her belly drop away, the seaside roller-coaster experience, except that here she was no child. There was no sand, no squinting sunshine, no erupting laughter.

Now as you know, I don’t love text that overuses physical statements as a way to describe emotion, but that’s because overuse of anything is bad, and because the statements tend to be very thin (mouth contorting, chest shuddering, etc). If you don’t overuse the statements and enrich the ones you do make, there’s not an issue.

Notice that here, we have Talia noticing something about her physical state – it’s not an external observation. But both things are fine.

Physical statements: external observation

Colour rushed into Talia’s face. She turned her head abruptly to prevent the other woman seeing but Asha was, in any case, more interested in the case of funerary amulets.

Here, we’re only talking about physical changes that are apparent on the outside, and that snippet is fine too. It doesn’t go very deep and, for my money, it feels like a snippet that would best go after a more direct statement. “Talia felt a surge of jealousy, anger almost. Colour rushed into her face, and she turned her head …”

Dialogue

“Daniel?” said Talia. “But he’s so much younger. I really doubt that he’d …”

Dialogue conveys emotion. It can also provide text and subtext in one. So here, the overt meaning is Talia’s doubt that a mid-thirties Daniel could fancy a mid-forties Asha… but the clear sub-text is a catty jealousy on Talia’s part. And readers love decoding those subtexts, so the more you offer them, the better.

Direct statement of inner thought

“Daniel?” said Talia. “But he’s so much younger. I really doubt that he’d …”

Doubt what? That he’d fancy the glamorous, shaggy-haired Asha, with her white shirts and big breasts and pealing laughter?

The second bit here is a direct statement of Talia’s actual thought. We could also have written:

Doubt what, she wondered. That he’d fancy …

That inserts a “she wondered” into things, but as you see, we can have a direct statement of her thoughts with or without that “she wondered”. Either way, it works.

Memory

Talia remembered seeing the two of them, at conference in Egypt. Holding little white coffee cups on a sunny balcony and bawling with laughter at something, she didn’t know what. Asha’s unfettered, unapologetic booming laughter and all the sunlit roofs of Cairo.

That doesn’t quite go directly to emotions, but it half-does and we could take it nearer with a little nudging. And, for sure, if you want a rounded set of tools to build out your emotional language, then memory will play a part.

Action

When Asha spoke, Talia had been holding a small pot in elaborately worked clay. It would once have held a sacred oil with which to anoint a new bride. Talia felt Asha looking sharply at her, at her hands, and when she looked, she saw the pot was split in two, that she’d broken it, now, after two thousand three hundred years.

OK, is that a bit on the nose? Breaking a marriage pot. Well, maybe, but it’s better than quaking, clenching and contorting all the time.

Use of the setting

They were in the vault now, marital relics stored in the shelves behind them, funerary relics and coinage on the shelves in front. Leaking through the walls from the offices next door, there was the wail of Sawhali music, the mourning of a simsimiyya.

At one level, that snippet is only talking about hard physical facts: what’s stored on the shelves, what music they can hear. But look at the language: we have marital and funerary in the same sentence. The next sentence brings us wail and mourning. This is a pretty clear way of saying that Talia’s not exactly joyful about things. Every reader will certainly interpret it that way.

And there are probably more alternatives too, and certainly you can smush these ones up together and get a thousand interesting hybrids as a result.”

Maris Kreizman has put some advice (for herself) on the Literary Hub website dated two days ago.

Maris Kreizman hosted the literary podcast, The Maris Review, for four years. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the New York Times, New York Magazine, The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Esquire, The New Republic, and more. Her essay collection, I Want to Burn This Place Down, is forthcoming from Ecco/HarperCollins.

She says, “Today I have my very first press event for my new book, which is out in July. I, along with three other wonderful Ecco authors, will take part in a lunchtime Zoom meeting with various members of the media and booksellers, during which we’ll be interviewed by Ecco’s associate publisher. I’ve been thinking a lot about what to say, and how to talk about my book in general.

I will not use this space to workshop anything, I promise. I’m not here to sell this book to you. But I do think my many years as a books journalist has primed me to understand what makes for a good talk, and I want to tell you about what I think works, while also reminding myself. Stage fright is real, after all.

I won’t have a script, just a few notes. I know how important it is to actually have a conversation, and that means being present and listening to what other people are saying, too.

The goal is to talk about the book in more detail than the marketing copy that my editor so carefully crafted for me, but to still be pithy and precise. The book has gone through so many iterations, and I have to have a handle on what it is now, after many rounds of edits and much feedback from my agent and editor and a few trusted friends.

In my career covering books, in podcasts and in print, I’ve conducted hundreds of author interviews, and the very best ones featured writers who were able to make a tight, cohesive narrative out of, well, the narrative they’d already written. As an author, getting the story right is the most important part of writing a book, but getting the story of the story right is the most important part of promoting it, of getting readers to want to buy it.

Often the authors who have the best grasp on the concept of storytelling to sell their own work are also teachers, the ones who are used to speaking to an audience in classes and keeping their attention until the end of the session. The biggest pros I’ve encountered have four or five stories that they can trot out for any occasion when they’re talking about the book. Does this mean that every article or interview they do is entirely original? Absolutely not. Do average readers read every single piece of press that’s written about a particular book, even the ones they’re interested in? Absolutely not.

It has just about always been the job of the author to help sell the book long after they’ve finished the job of writing it. I think we like to pretend that in the past authors could simply write a book and then keep their heads down, letting their publishers take care of getting the word out. To be fair, before the technological changes of the 21st century (namely social media) authors could be more passive in the promotion of their books—Philip Roth never had to connect with readers on Twitter or do a bunch of podcasts, after all. But he did have to, in interviews and at bookstore talks and signings, make readers want to buy what he was selling.

Now, in a landscape where books don’t get tons of traditional media coverage and social media overall gets less and less reliable, it’s more important than ever for authors to take an active role in talking about their books (reminder: we love our in-house publicists and marketing gurus, but there’s only so much they can do on a tight schedule with a punishing work load). As icky as it may feel to have to be the chief salesperson of one’s own book as well as the writer, who else has more of a vested interest in making sure the book finds readers?

My hope is that after I’ve discussed my book today, more people in the industry will actually get a chance to read it, and they’ll be able to tell me what they think my book is about. They have more distance from the work than I do, and I welcome their interpretations. In fact I welcome any good faith takes on my book, although because I am also the chief protector of my own sensitive feelings, I may not have the emotional bandwidth to consider them all.”

I agree with what Maris says, and I’d like to add some points:

Harry Bingham of Jericho Writers made in interesting point about unsolved mysteries in his Friday email of 6 December 2024. He calls it the easiest technique in fiction.

Harry said, “Lots of things in writing are hard. One thing in particular is very, very easy… but it’s astonishingly neglected by a lot of writers.

Here’s an example of getting something wrong, using an extract I’ve invented for the purpose. In my mind, this extract might stand at the start of a novel, but it could be anywhere really.

So:

Dawn woke her – dawn, and the rattle of trade that started to swell with it. Barrels being rolled over cobbles, a cart arriving from the victuallers’ yard, men starting to bray.

It had been a cold night and promised to be a cold morning, too. Her feet found the rag mat next to the bed. She washed hands and face briefly, and without emotion, then lifted her nightgown and began to bind her breasts, with the white winding strip she always used. Round and round, flattening her form.

She continued to get dressed. Blue slops. Bell-bottomed trousers, a shirt, a waistcoat, a blue jacket, loose enough for her shoulders to work. Just for a moment, she looked at her hands. They’d been soft once, and were coarse now, hardened off by the scrambles up rigging, the hard toil on ropes.

Caroline – Charles as she was known to her fellow ratings – had been forced to take work as a man when her father died two years ago, right at the start of this new war against Napoleon. She had tried taking work as a seamstress, but the pay had been poor, and she had a younger sister always sickly to look after. In the end, she had found herself forced to dress as a man and work as a man, here at the great bustling port of Portsmouth…

I hope you can see that this passage is kinda fine… and kinda fine… and then disastrous.

The first paragraph here is fine: it starts to establish the scene.

The second paragraph is intriguing: why the flipping heck is this woman (clearly not a modern one) so keen to flatten her chest?

The third paragraph inks in a bit more of the mystery: OK, so this woman works on ships of some sort in the eighteenth or nineteenth century. So why is she disguising herself as a man?

And then –

The disaster –

The writer makes the horrendous mistake of answering that question. The story was just beginning to make fine headway. We wanted to grip our reader and thrust them forwards into the story. Our first three paragraphs set up a fine story motor, which was already starting to chug away. Then by completely solving the mystery, we destroyed almost every shred of momentum we had.

By the end of that extract, we still have an interest in seeing what happens to this woman, but we don’t yet know her very well as a character. We can’t at this stage care very much about her. But we did care about that mystery. And the author just ruined it.

The lesson here – and the easiest technique in fiction is – take it slow. If the reader wants to know X, then don’t tell them X.

That’s it! That’s the whole technique.

A much better approach here would have been to simply follow Caroline/Charles’s morning. I’d probably have given her some kind of problem to solve. Perhaps, she owes an innkeeper money that she doesn’t have and needs to slip away unseen. Or she has to collect some belongings from one part of town but has to get back to her ship in order not to miss the tide.

That way, one part of the reader is asking, Will she get back to her ship in time? But that’s just a top layer to the more interesting underlying question of Why is she disguised as a man?

Indeed, we’ll study the whole rushing-about-town episode with extra interest, because while we’re not that fussed about whether she misses the tide or not, we are interested in that second question – and we read about these ordinary story incidents as a way to uncover clues about the bigger issue.

The key fact here is that readers love solving mysteries. They like reading a text to find clues and hints and suggestions that lead them to an answer. I think for most readers that process has an extra impetus if the mystery is embedded in something very personal to a key character.

So the technique you need to adopt is:

The easiest technique in fiction.

The Daily Telegraph has an article in its 29 December 2024 issue which I find distressing. (I could not find an author attribution.)

Homer, author of the Iliad and the Odyssey classics

The article says, “Homer’s epic poems The Iliad and The Odyssey have been hit with trigger warnings by a university for “distressing” content.

The University of Exeter has come under fire after telling undergraduates they may “encounter views and content that they may find uncomfortable” in their Greek mythology studies.

In what has been branded as a “parody” and “bonkers”, students enroled on the Women in Homer module are told material could be “challenging”.

With references to sexual violence, rape and infant mortality, undergraduates are also advised they should “feel free to deal with it in ways that help (eg to leave the classroom, contact Wellbeing, and of course talk to the lecturer)” if content is “causing distress”.

However, the advice, which was obtained by the Mail on Sunday via Freedom of Information laws, has been ridiculed by both classics-loving Boris Johnson and experts alike.

The Iliad depicts the final weeks of the ten-year siege of the city of Troy by Greek city-states, while The Odyssey describes Odysseus’s successful journey back to Ithaca, set over multiple locations, timelines and alternative homelands.

Mr Johnson, who read classics at the University of Oxford and is a fan of Homer, said the ancient works provided the “foundation of Western literature”.

Reacting to news of the university’s warning, the former prime minister described the policy as “bonkers”, telling the paper: “Exeter University should withdraw its absurd warnings. Are they really saying that their students are so wet, so feeble-minded and so generally namby-pamby that they can’t enjoy Homer?

“Is the faculty of Exeter University really saying that its students are the most quivering and pathetic in the entire 28 centuries of Homeric studies?”

Historian Lord Andrew Roberts said students shouldn’t be “wrapped in cotton wool and essentially warned against ancient but central texts of the Western canon”.

Frank Furedi, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent, added: “A university that decides to put a trigger warning on Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey has become morally disoriented to the point that it has lost the plot.”

Jeremy Black, the author of A Short History Of War, said the measure “can surely only be a parody”.

A spokesman from the University of Exeter told The Telegraph: “The University strongly supports both academic freedom and freedom of speech, and accepts that this means students may encounter views and content that they may find uncomfortable during their studies.

“Academics may choose to include a content warning on specific modules if they feel some students may find some of the material challenging or distressing.

“Any decision made to include a content warning is made by the academics involved in delivering the modules, and these help ensure students who may be affected by specific issues are not subjected to any potential unnecessary distress.”

The warnings on Homer’s work come amid an increasing number of works being slapped with trigger warnings.

Last week, it emerged that John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men was removed from the Welsh GCSE curriculum for the “psychological and emotional” harm caused by its racial slurs.

In October, the University of Nottingham received similar criticism for warning students of The Canterbury Tales’ “expressions of Christian faith”.

Earlier this year, Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland were amongst a collection of children’s stories that were handed trigger warnings for “white supremacy” at York St John University.

In 2023, a disclaimer was added to the republishing of Nobel Prize-winning Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Whilst deciding not to censor the book, publisher Penguin Random House’s note made clear the reissue did not constitute an “endorsement” of Hemingway’s original text.”

I remember that as a child my mother reading both the Iliad and the Odyssey to me and that I particularly enjoyed them, knowing that they had been written 2,800 years ago.. Are today’s young adults really so vulnerable to distress? If so, trigger warnings are necessary for 90% of the current news!