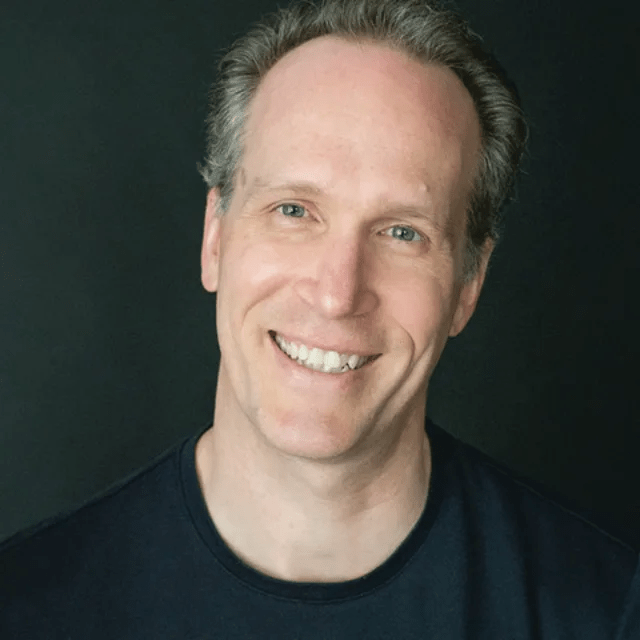

I admire Frank Gardener, the author of this novel, for his bravery in recovering from severe injuries while he was reporting for the BBC in Saudi Arabia. But not only has he survived, but he has largely overcome his mobility impairment by becoming the BBC’s security reporter

and he is a best-selling novelist. Well Done, Frank!

Frank Gardener

Francis Rolleston Gardner OBE (born 31 July 1961) is a British journalist, author and retired British Army Reserve Officer. He is currently the BBC’s Security Correspondent, and since the September 11 attacks on New York has specialised in covering stories related to the War on Terror.

Gardner joined BBC World as a producer and reporter in 1995, and became the BBC’s first full-time Gulf correspondent in 1997, before being appointed BBC Middle East correspondent in 1999. On 6 June 2004, while reporting from Al-Suwaidi a district of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Gardner was seriously injured in an attack by al-Qaida gunmen, which left him partially paralysed in the legs. He returned to reporting for the BBC in mid-2005, using a wheelchair or a frame. He has written two non-fiction works as well as a series of novels featuring the fictional SBS officer-turned MI6 operative Luke Carlton.

This novel is set in England, China, Taiwan and vicinity in the present. The main characters are Dr Hannah Slade, a full time climate scientist at Imperial College, on a ‘collection assignment’ for MI6; Luke Carlton, case officer with MI6; and Jenny Li, intelligence officer with MI6. Hannah is apparently in China to attend a climate conference, but her real mission is to collect a small microchip from a senior agent with access high in China’s military. The microchip contains details about China’s plans to invade Taiwan. She meets the agent, receives the microchip and hides it behind her missing wisdom teeth. Almost at once she is captured and moved to Macau by criminals of a Chinese triad. When MI6 realises that Hannah has gone missing, they send Luke and Jenny to find her and the microchip. Luke and Jenny follow a lead to Macau, where they realise that a powerful triad is involved, and is in the process of moving Hannah to Taiwan. An attempt to recapture Hannah on the sea fails. Luke and Jenny go to Taiwan where they investigate a lavish temple,which turns out to be owned by the shadowy triad boss, Bo. Bo’s intention is to sell Hannah to the highest bidder: China, Taiwan, USA or the UK. Before Bo is able to act, the three Brits escape. Hannah hands the microchip to Luke for safe keeping. Jenny and Luke make good their escape, but they have to leave the injured Hannah behind. When they are back in the UK, Luke and Jenny learn that Hannah, who has fallen into the hands of China, is accusing MI6 of deserting her.

I had expected this novel to be about a fictitious invasion of Taiwan, but the only activities by the Chinese military are the firing of a hypersonic missile by a Chinese warship, the taking over of a tiny Taiwanese island, and preparations to take over Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. This was a bit disappointing, but if Gardener had written what he doubtless knows about an actual takeover, he would have doubtless been censured by the UK government, so the triad had to be inserted as the bad guys.

The book is well written, credible and suspenseful.