There is an intriguing article by Carter Wilson on the Writer’s Digest website on how and why to use an unreliable narrator in fiction – dated 29 January 2025.

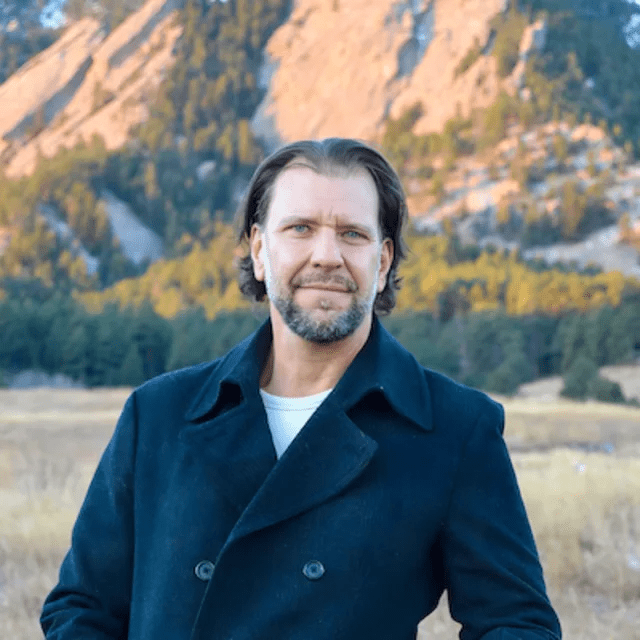

Carter Wilson is the USA Today bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed, standalone psychological thrillers. He is an ITW Thriller Award finalist, a five-time winner of the Colorado Book Award, and his works have been optioned for television and film. Carter lives outside of Boulder, Colorado.

Carter Wilson

Carter says, “Crafting a convincing unreliable narrator might be one of the most difficult things a thriller writer does. Of course, a narrator doesn’t have to be unreliable. A perfectly dependable narrator is often just what the thriller reader needs. A voice of reason and stability thrust in the midst of chaos. Sometimes we want that level-headed hero to guide us through those dangerous waters.

But sometimes…

Sometimes we, as readers, don’t want stability. Sometimes, in the middle of that chaos, we don’t want to believe anyone, including the voice that’s at the helm. Occasionally the fun is figuring out who to trust, if there’s anyone to trust at all. The best thrillers are often the ones in which the protagonist is not only fooling the reader, but themselves as well.

I specialize in writing unreliable narrators, and when I try to dissect why exactly that is, I can think of a few reasons. There are likely many more, but that may take thousands of dollars of therapy to tease out. But top-of-mind, these reasons stand out.

1) I don’t know what I’m doing.

I mean that with 82% sincerity. I don’t outline, and usually I only have the vaguest notion of a plot idea, or sometimes I only know the first chapter. My stories unfold to me one day at a time, which means my narrator is just as lost as I am. I’m writing from my subconscious, which lends itself to a labyrinth of twists and turns, many of which the narrator has created for themselves. Simply put, my narrator is unreliable because the author is unreliable.

2) Life is unreliable.

If one really considers what makes a narrator unreliable, a few choice adjectives pop up. Deceitful, delusional. In denial. Okay, do those words not describe all of us, at least in some part of our lives? Unreliable is honest. What’s not honest is a hero who can do no wrong, always has the answers, and is always willing to save others before themselves. Is this an admirable protagonist? Yes, of course. But it makes for a helluva boring thriller.

3) The intimacy of the POV.

I typically write from a first-person, present-tense point of view. That means I’m seeing the world through my narrator’s eyes, moment by moment. This makes writing an unreliable narrator most effective, because the reader experiences the thoughts and actions as the protagonist does, and offers a fractured, almost stream-of-consciousness narration. What’s more unreliable in our daily lives than our swirling thoughts, our sudden fears, our whimsical and wholly unattainable daydreaming?

Striking a perfect balance

Writing an unreliable narrator brings me great joy, because I know readers will be lured into thinking one way until suddenly they’re forced to face an altogether different reality. But it’s also a tricky way to write, and the writer has to strike the perfect balance between believability and deus ex machina. An unreliable narrator shouldn’t be approached as a literary device; rather, a narrator’s unreliability should be an organic result of who they are and the decisions they make.

No author should set out and think to themselves, “I’m going to write an unreliable narrator.” That leads to clumsy and shoehorned writing. Rather, the author should pen the novel as it occurs to them from the subconscious, and only after reading the first draft should they themselves realize their protagonist is not to be trusted. The best writing comes from ephemeral, naturally occurring thoughts rooted in decades of life experience and keen observation. The worst writing comes from market-conscious intentions.

In my newest release, Tell Me What You Did, my protagonist Poe Webb’s unreliability is less a device than a simple fact of life. She lies to the audience because she lies to herself. Poe committed a horrible crime in her past, and though that experience has largely informed who she is in the story, she’s suppressed the memory enough that she struggles to even admit to herself what she did until events force her to reckon with her past actions. Her unreliability is, at its core, human.

The final key in writing an unreliable narrator is to avoid coyness. Too many times an author hints over and over that their protagonist is not to be trusted, building up an anticipation that’s so great the payoff never quite satisfies. Rather, the best unreliable narrators are those who never wink at the camera, and when they look into the mirror they’re just as convinced as we are that the person in front of them is telling the truth.

Like I coach all my students, write from the heart, from the soul, from instinct, from the subconscious. From that perspective, an unreliable narrator is not a trick but rather a fully formed individual who is convinced they are doing the right thing, despite all evidence to the contrary. This results in a hero—or anti-hero—who is, above all else, uniquely flawed and morally gray. Just like all of us.”