There is an essay on the Electric Literature website about how one writer confronted her aging process; it in titled ‘Mirrors Tell the Truth but Not the Whole Story’, and it’s written by Stephanie Gangi.

Stephanie Gangi is a poet, novelist, short story writer and essayist living and writing in New York City. Her debut novel, The Next, was published by St. Martin’s Press and her second, Carry the Dog, from Algonquin Books in November 2021 and has garnered early praise. Gangi’s work has appeared in, among others, Arts & Letters, Catapult, LitHub, Hippocrates Poetry Anthology, McSweeney’s, New Ohio Review, Next Tribe, and The Woolfer. She’s working on her third novel, The Good Provider.

Stephanie Gangi

“Years ago I wrote a poem, “Mirror Window.” The gist of it was that I kept mixing up the words, mirror and window; I said one when I meant the other. It was alarming, I was not yet forty, too young to lose language. My daughters noticed and teased me about being old, as daughters will, and I wrote about that, kind of a circle of life thing.

I’ve gone back and read the poem and it’s not bad, but like all my writing at the time and from years before, from my teens, I filed it away and distracted myself with being young: sex-and-drugs-and-rock-and-roll, i.e., men, and then marriage and a shiny, happy family in a house on a hill. I have conflicted feelings about this. On the one hand, I was distracted from writing by love, lucky me; on the other, love was conditional or finite, humans being human, especially me. The writing was a constant, but me as a writer was something—someone—I could not see. I thought of it as a hobby.

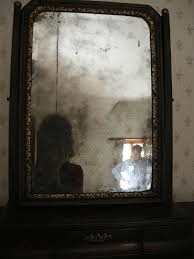

In my late 40s, I tried “Mirror Window” again. This time it took the form of an essay, which came about because I was in possession of a large, antique mirror that I didn’t like but couldn’t get rid of. Let me go back.

I got the mirror when my mother died a decade earlier, not just my mother but my father too, he in March and Ma in June, both suddenly, neither yet seventy or sick. I was thirty-seven years old, an only child, or an adult only child, and a mother myself, in a complicated marriage. I was left with a split level to sell in the dead middle of Long Island. The contents were all mine, down to the coffee cup in the sink with Cherries in the Snow lipstick left on its rim. Consequently, the objects and furnishings and jewelry held—hold— outsized sentimental value.

Time passed, the parameters shifted. Love was indeed finite. My marriage ended and my little family reconstituted itself. We moved, with the mirror, to where we fit better with one less of us. That’s when I decided to paint its frame, give it a new look for my new life. I laid it out on a tiny patch of city yard on a sunny day, and in the course of sanding it down, I was on my hands and knees hovering over my reflection, focused on the task, not noticing myself. And then I did, and I saw how I’d look if I were on top of someone. How I looked during sex was on my mind at the time—I was a divorcée, it was still called that—because I was having a lusty adventure with a man seventeen years my junior. I was on top regularly.

The vantage point over my reflection showed my hair hanging in lank curtains on either side of my face, red with exertion. Gravity plus the sanding effort yielded sagging and swaying. The word “jowls” made itself manifest. I’d never looked my age before, but kneeling over this mirror, I sure did.

The distracting fling with this guy had turned into foolish fantasies about a life together. Once during pillow-talk, we did that thing of revealing something each had never told anyone else. My dark secret: Botox. We both reveled in our age difference but the truth was, I’d been trying to hide it. His dark secret? He admitted that he would stay a relationship’s course until someone new came along to provide him with a reason to leave. I knew this was true. It was the case with us; I had recently been the new one. “Mirror Window” was an essay about heartbreak. Once again, I filed my work away.

It turned out there was more to it than heartbreak. It turned out that refinishing the mirror gave me a window into a future with him I could not countenance, in both senses of the word—countenance like face and countenance like support. The truth is even if I had not sagged over the mirror that day, I was already worried about being where I am now, here in my sixties with a younger man who’d all but warned me he’d be watching for the exit. People do tell you who they are, and you should believe them, and he did, and I did.

So I reframed. My longest, truest commitment, to writing, was never a hobby. It is what I do and who I am. First novel at 60, forthcoming novel at 65, third in the works. Now and then the hot chill of regret passes through me. I should have started sooner. I should have been less high, less young, less seductive and less seduced, less distracted. Well, wait. That’s not right. I was full of life and love, and sorrow, joy, and disappointment—the open heart. Regret is beside the point. I know there’s no grace in that.

Let me keep going.

I am still new at being me, the writer. I have so many ideas that I cast around too long before I settle on something. A writer friend advised, “Just write about what you always think about.” Mirrors and windows. It’s not a sophisticated metaphor, but it is simple, it is effective. In my work, my women think a lot about how to age gracefully even as they learn to recognize themselves in their new old faces. They stare into their bathroom mirrors and wonder what to do about the jowls even when they are nobody’s lover, let alone on top. They too are startled when they catch an unexpected reflection in a shop window.

Two crazy things happened recently on the same locked-down day. I went through my apartment in a pandemic-fueled mission to spruce things up. I decided to repaint the frame on my mother’s mirror again, it’d been a long time, and I wanted it to match a smaller mirror that I bought at a yard sale in Montauk thirty years ago, with an infant in my arms and a toddler hanging from my legs. I was inspecting this smaller mirror and I was surprised. Oh. It’s a window frame. A window frame, fitted with mirrored squares instead of clear glass. I’d had it for so long I didn’t register it anymore, even though I passed it several times a day. I actually own a mirror window.

Not an hour later, I picked up a package containing the manuscript of my new novel—about distorted memory, accepting who you once were, and recognizing who you are now—from my editor. I poured some red wine and sat down, thrilled and grateful to see his old-school, handwritten edits on manuscript pages. On page 178, there was a strong delete mark through the word “window,” and his caret and note indicating it should be replaced with the word “mirror.” I’d done it again.

Mirror window. It wasn’t a mix-up, I hadn’t lost language. I was telling myself something I couldn’t hear yet. I was showing myself something I didn’t see yet. It’s like the two words were saying, and kept saying, Look inside, look outside, write it down, make it your life.

My daughters are now old enough to tease each other about getting old; I’ve aged out of the joke but I’ve revised the old poem, newly titled “Last Laugh,” wherein I give myself the final word, a circle of life kind of thing. I revised the saggy-jowls essay, and this is how it’s ended up: published, not filed away. I’m tunneling into the third novel, and in an opening scene my protagonist is holding a chaotic yard sale, everything must go, including her dead mother’s furniture, including a window frame fitted with mirrors for panes, just like mine.”