I have another confession to make: I didn’t bother to read this book (also) when it was first published, because I was put off by the title and the hype. But when I was preparing my summer reading list, I decided to add it. In fact, I actually ended up buying the first three books in the original Millennium Trilogy, because they weren’t listed individually on Amazon.co.uk. But before I got there I bought a series of three Millennium books on Amazon.it. When they arrived, I saw that they were books 4-6 by a different author, who was ‘carrying on’ Stieg Larsson’s (the original author’s) ‘footsteps’. I read the first 100 pages of book no. 4, thought ‘this is rubbish’, and put books 4-6 in the bin. (For those of you who don’t know, Stieg Larsson, the original author took the complete manuscripts of book 1-3 to the publisher, and died of a heart attack before he could see them in print.) My view, having read 100 pages of book 4, is that the publisher made a hasty decision to satisfy a demand for more Millennium without qualifying the author and with inadequate editing.

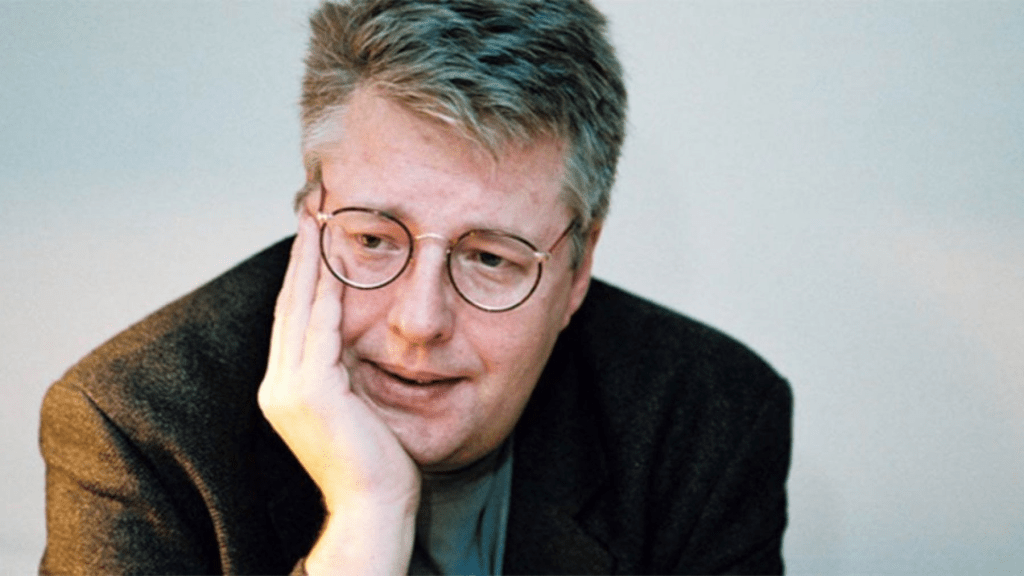

Stieg Larsson

Wikipedia says: “Karl Stig-Erland “Stieg” Larsson, Swedish: 15 August 1954 – 9 November 2004) was a Swedish writer, journalist, and activist. He is best known for writing the Millennium trilogy of crime novels, which were published posthumously, starting in 2005, after he died of a sudden heart attack. The trilogy was adapted as three motion pictures in Sweden, and one in the U.S. (for the first book only). The publisher commissioned David Lagercrantz to expand the trilogy into a longer series, which has six novels as of September 2019. For much of his life, Larsson lived and worked in Stockholm. His journalistic work covered socialist politics and he acted as an independent researcher of right-wing extremism.

There are two principal and quite unique characters in this novel: Lisbeth Salander, tiny, mid-twenties, brilliant computer geek, anti-social, severely abused as a child, and Mikael Blomkvist, mid forties, bright, moralistic, attractive publisher of the journal Millennium, in Stockholm. Both are dedicated and very competent investigators in their respective fields: Lisbeth: personal and corporate security; Mikael: business. At the outset, Mikael has been convicted of libeling the billionaire industrialist Wennerström; he serves a three-month prison term. He is offered a one-year freelance job to write the history of the Vanger industrial family, but he knows that his real assignment is to discover who murdered the grand-niece of the patriarch, Henrik Vanger forty years ago. Impressed with her work investigating him for Henrik Vanger, Mikael hires Lisbeth to use her computer skills in investigating the Vanger family. They discover that Michael Vanger, the current CEO of Vanger Industries, and the brother of Harriet Vanger, the girl who disappeared, can be linked to several violent murders of women, but not to his sister disappearance. Lisbeth saves Mikael from death at the hands of Michael, whom he has confronted. Michael escapes, but pursued by Lisbeth and he commits suicide by driving head-on into a truck. Knowing that Michael did not kill Harriet, Lisbeth and Mikael trace Harriet to a sheep farm in Australia where she is the owner/manager. Lisbeth unearths some terrible dirt which destroys the Wennerström empire, and, incidentally, she siphons off several billion krona into her own account.

This book is very hard to put down. In fact, I kept it close at hand so that I could read a page or two when I had a chance. Larsson drew his characters clearly and persuasively, so that they stand out in your mind. He also went to the trouble of setting each scene so that the reader feels s/he is there. But above all, he was a master at creating and maintaining tension about what will happen next to these characters about whom the reader really cares. He also skillfully leads the reader into anticipating X, when a surprising Z actually occurs. Great creativity!