This article appears on the Copyblogger website and was written by Dean Rieck. He is “Copywriter and Consultant for Direct Mail and Direct Marketing”

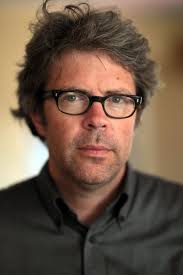

Dean Rieck

I agree with much of what he says about “brilliant writing”, but not all. Perhaps our divergences are mostly about differences in perspective: advertising copywriter vs author. His blog says:

“Here are 11 ways you can start sounding brilliant:

1. Have something to say

This makes writing easier and faster. When you have nothing to say, you are forced to write sentences that sound meaningful but deliver nothing. Read widely. Take notes. Choose your subjects wisely. Then share your information with readers.

2. Be specific

Consider two sentences:

- I grow lots of flowers in my back yard

- I grow 34 varieties of flowers in my back yard, including pink coneflowers, purple asters, yellow daylilies, Shasta daisies, and climbing clematis

Which is more interesting? Which helps you see my back yard?

3. Choose simple words

Write use instead of utilize, near instead of close proximity, help instead of facilitate, for instead of in the amount of, start instead of commence. Use longer words only if your meaning is so specific no other words will do.

4. Write short sentences

You should keep sentences short for the same reason you keep paragraphs short: they’re easier to read and understand. Each sentence should have one simple thought. More than that creates complexity and invites confusion.

5. Use the active voice

In English, readers prefer the SVO sentence sequence: Subject, Verb, Object. This is the active voice.

For example:

Passive sentences bore people.

When you reverse the active sequence, you have the OVS or passive sequence: Object, Verb, Subject.

For example:

People are bored by passive sentences.

You can’t always use the active voice, but most writers should use it more often.

6. Keep paragraphs short

Look at any newspaper and notice the short paragraphs. That’s done to make reading easier, because our brains take in information better when it’s broken into small chunks. In academic writing, each paragraph develops one idea and often includes many sentences. But in casual, everyday writing, the style is less formal and paragraphs may be as short as a single sentence or even a single word.

7. Eliminate fluff words

Qualifying words, such as very, little, and rather, add nothing to your meaning and suck the life out of your sentences.

For example:

It is very important to basically avoid fluff words because they are rather empty and sometimes a little distracting.

Mark Twain suggested that you should “Substitute damn every time you’re inclined to write very; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.”

8. Don’t ramble

Rambling is a big problem for many writers. Not as big as some other problems, such as affordable health insurance or the Middle East, which has been a problem for many decades because of disputes over territory. Speaking of which, the word “territory” has an interesting word origin from terra, meaning earth.

But the point is, don’t ramble.

9. Don’t be redundant or repeat yourself

Also, don’t keep writing the same thing over and over and over. In other words, say something once rather than several times. Because when you repeat yourself or keep writing the same thing, your readers go to sleep.

10. Don’t over write

This is a symptom of having too little to say or too much ego. Put your reader first. Put yourself in the background. Focus on the message.

11. Edit ruthlessly

Shorten, delete, and rewrite anything that does not add to the meaning. It’s okay to write in a casual style, but don’t inject extra words without good reason. To make this easier, break your writing into three steps: 1) Write the entire text. 2) Set your text aside for a few hours or days. 3) Return to your text fresh and edit.

None of us can ever be perfect writers, and no one expects us to be. However, we can all improve our style and sound smarter by following these tips and writing naturally.”

I agree with 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11.

3. Choose simple words:

Use of simple words is probably fine for advertising where clarity and conciseness are essential. But when writing fiction, and when one is trying to paint a complex picture of fact, feelings and suppositions, simple words are rarely fully effective. Maybe an unlikely combination of two or three special words is necessary to convey the mixture of fact and feelings.

4. Write short sentences:

Here again, punchiness isn’t necessarily what we want. Short sentences can lack lyricism or intellectual interest. They can be boring if repeated. Use of some longer sentences can keep the reader interested.

5. Use the active voice:

OK, but switch now and then to keep the reader alert.

6. Keep paragraphs short:

I believe that paragraphs should be used as a clue to the reader that the action is changing: different time, different setting, different characters. There is no other reason to break up the text other than that a paragraph longer than one page can make it feel to the reader that the reading is becoming laborious!